By Hillary Kaplowitz – Published in Kiai Echo, Winter 2010

As 2009 wound to an end, I encouraged my students to reflect on all they accomplished during the year. I also challenged them to find ways to recognize and improve those areas of training they have been neglecting. Most importantly, I instructed each of them to set an intention for the next year.

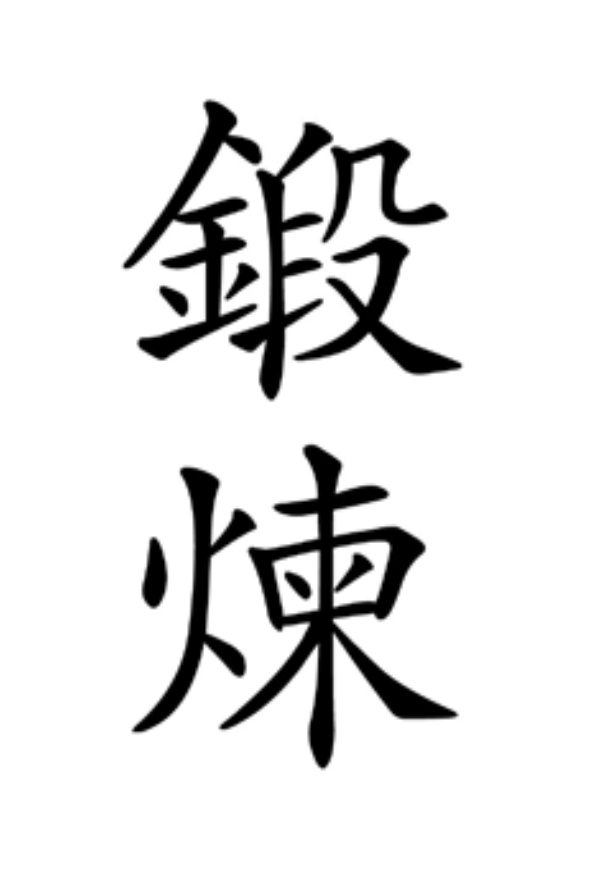

December’s theme at our dojo was Tanren, which I chose in order to emphasize the concept of training and discipline as keys to success in the study of martial arts. A notable aspect of tanren is the idea of forging. At its core, success in our practice comes from practice itself. Hard work is the vehicle for progression and transformation. Another inherent quality of tanren is polishing and, as one of my students pointed out, polishing implies a process that is never complete. There is always work to do, so do the work.

Tanren was one of twelve themes I selected for my dojo to study over the course of the past year, one term per month. The genesis of these themes came from a discussion with Prof Ball where he asked a number of people to identify the basic underlying principles inherent in all Danzan Ryu techniques. At the time,

I didn’t know that he and the professors were working on developing the Kihon. I decided to make this an assignment for myself and worked to develop a set of terms that together would highlight the important concepts in our art.

While the Kihon describe the basic qualities and principles inherent in every technique, I decided to select key Japanese martial arts terms that could help focus the scholarly side of our martial arts study. I wanted the terms to have the quality of simplicity but also have the ability to convey a broad width and depth of concepts in the same way that an okugi or ogi (secret teachings or principles) conveys straightforward concepts that are easy to comprehend superficially but difficult to manifest, yet alone master. Which brings us back to tanren.

The process of selecting and honing the terms down to a list of twelve was a valuable exercise for my training and I decided that they would be useful for my students as well. My sensei, Prof Hudson, often sets a theme for the year, which helps to focus our training. I decided to do a similar thing and use one theme per month. I had twelve so it would work out perfectly. Here is a month-by-month account of the themes we studied in 2009. I call them the Tanren Ju Ni Hon or the 12 Principles for Training.

Tanren Ju Ni Hon – 12 Principles for Training

January – In/Yo

In/Yo (or Yin/Yang in Chinese) was chosen as the first term to highlight the applied concept of duality in all things. This fundamental concept helps us understand interactions within our world. We looked at the contraction and expansion within techniques, tightening and releasing, and the idea of responding to a push with a pull and vice versa as core principles of action within our art. We spent time looking at the Uke/Tori relationship as an example of In/Yo and the idea that techniques have two equally important aspects.

February – Yawara (Ju)

Our art is based on the core principle of going around conflict. Our techniques require us to be supple and yield to force, never to resist it. We strive to develop our techniques so we do not rely on strength. We looked at techniques with circular motions and that redirected energy and tried to find ways to go where the other person was not. We studied the concept of adaptability and having a flexible body and mind – to cultivate the mental state of Junanshin – an open and receptive mindset.

March – Sutemi

Focusing on sutemi allowed us to further develop the ability to adapt and to yield. We spent time working on receiving techniques and improving our skills taking falls. But focusing on sutemi also challenged us to work on the mental idea of giving up to gain, to give up a bad position for a better one. We investigated the idea of going with motion to gain control, and looked at how sutemi challenges us to free ourselves from attachments and abandon the self.

April – Kamae

Posture and frame are essential to good technique. Our goal is to strive to maintain our balance while we disturb the balance of others. We discussed our stance and moving while maintaining our center. We looked at how proper posture gives us the ability to generate power from our waist. Kamae goes beyond just having proper posture, it is an outward manifestation of our presence and a calm alertness before action. The word not only implies a structure but also a feeling of care and attention. Furthermore we looked at how our physical equilibrium informs our mental equilibrium and vice versa. Maintaining integrity is much more than just keeping your balance.

May – Ma’ai

The monthly themes were structured in a particular order so they could build on one another. We started with some global principles and worked towards inculcating them in our techniques. It was natural to go from kamae to ma’ai, from our own integrity to our relationship to another person. Ma’ai let us focus on proper distancing, position within techniques, entering and getting off the line. Ma’ai is about relationships, whether it be in space or time, a gap or a pause. Inherent in ma’ai is the idea of timing, of seizing opportunity and connecting with your partner in accord.

June – Kokyu

Coordinating our breath can help coordinate our actions and help to cultivate rhythm and flow in our motions. When we hold our breath we tighten, but if we can learn to breathe with our actions we naturally become more relaxed. Awareness of breath can help us with timing, either to be in sync with our uke or to take advantage of an opening. We also looked at how breath can help us develop our ki and practiced the kowami breathing exercise and chi gong as ways to cultivate our internal power.

July – Kiai

It was natural for us to move from the concept of kokyu and transition to kiai, which is also about coordination of breath with activity. But the key to kiai is concentrating one’s ki more than the exhalation or the shouting. The sound is an indicator of a good kiai – aligned body structure, focused intent and proper breathing. In some ways it is actually an expression of elation of a technique done well. In addition, kiai can be thought of as a method for organizing our mental and physical aspects. We strived to fill our techniques with ki, to make them vibrant and use our kiai to coordinate our motions and cultivate our awareness.

August – Tori

As jujitsuka we need to become experts at locking, binding and controlling. The mokuroku refers to the Chinese methods of seizing and capturing that influenced the development of jujitsu. To capture or catch is integral to locking. In fact the term for ancient policeman, torite, uses the same root. We focused on taking out the slack in all our techniques, worked on our gripping, and looked closely at the mechanics behind torque and torsion. We further discussed the idea of locking the mind and how that can capture a person, even if only for a moment, and the opportunity that presents.

September – Kuzushi

Our focus on kuzushi flowed naturally from tori as we moved from yawara based arts to the throws and projections of nage, oku, etc. We contrasted stability and instability by revisiting kamae and emphasizing that we want to always strive to maintain our balance while taking away uke’s stability. We looked at the multitude of directions of kuzushi and how to apply leverage and momentum as well as counterbalance and dynamic tension. Kuzushi can be thought of as the ultimate application of ju in that we should only throw people when they are about to fall down. The word kuzushi is more than just unbalancing, it is the process of physically or mentally manipulating uke through your own posture and body movements to a place where his stability is destroyed and he is unable to regain it, even if only for a moment – and then to capitalize on that moment.

October – Mushin

We next looked inward at the mental quality necessary to execute our techniques. The mind must be open and empty to achieve the quality that Prof Okazaki called kyoshin tankai – the ability to move without purposeless resistance. It is a state of mental clarity and enhanced perception produced by the absence of preconceived ideas, thoughts and emotions. We looked at how the “zone” in sports is a type of mushin. We practiced methods of quieting our mind and expanding our awareness with the goal of becoming fully present in the motion and approach the state of freedom of mushin.

November – Kime

Kime is very much connected to mushin. Kime is focus and concentration, intent and commitment and is integral to mushin. One way to see the connection is that mushin reflects a state of mind, while kime reflects a state of the body. A motion with kime is crisp, explosive and appropriate. It is based on technique and not unnecessary strength. Kime is about decisiveness and focus of one’s entire being on achieving the task at hand. We practiced our arts slowly and purposefully, feeling every nuisance of every motion, filling each part with ki and intention.

December – Tanren

The purpose of concluding the set of principles with tanren was to provide a vehicle for achieving the principles we discussed. The only way to succeed is through diligent, focused training and discipline. Through our training we temper, forge and polish, coming out the other side changed. Our study is not about acquiring techniques, it is about getting rid of clutter, about staying true to our principles, about staying on the path and letting our training transform us.

One of my favorite things about working with these themes is how we kept coming back to the kata arts of the system. I found myself repeatedly using the kata arts to illustrate an aspect of a theme.

For example, we were discussing kamae and looking at how in Akushu Ude Tori you must maintain your posture while breaking theirs. Then the next month, we were looking at ma’ai and once again I found myself using Akushu Ude Tori to illustrate the proper distancing. Each month we returned to our basic techniques but with a new insight and focus. The practice is the practice. We must do the arts over and over and over and over again but we must fill the practice with purpose and intent.

Going back to tanren, it is our duty as students of Danzan Ryu to find the secrets in the arts. To investigate, study and practice what we have been taught. The idea of creating themes is just one way to direct that process. Feel free to use or adapt this training method for yourself or your students. And make sure to let me know what you discover on your path.